Laurence Whistler was invited to design for Wedgwood in 1955, but only

two of his designs were adopted for production. This series, called

'Outlines of Grandeur', was one of the two. The series illustrates

British architecture through six periods of history. Each design shows

Whistler's background as a glass engraver and uses line effects to

create strikingly different designs. This plate features Britain's most

famous prehistoric remains, the Stonehenge megalith in Wiltshire. This

plate was made in 1955-6. This example has suffered some damage.

Thursday 28 June 2012

Tuesday 26 June 2012

Abri Castanet Vulva

We report here on the 2007 discovery, in perfect archaeological context, of part of the engraved and ocre-stained undersurface of the collapsed rockshelter ceiling from Abri Castanet, Dordogne, France. The decorated surface of the 1.5-t roof-collapse block was in direct contact with the exposed archaeological surface onto which it fell. Because there was no sedimentation between the engraved surface and the archaeological layer upon which it collapsed, it is clear that the Early Aurignacian occupants of the shelter were the authors of the ceiling imagery. This discovery contributes an important dimension to our understanding of the earliest graphic representation in southwestern France, almost all of which was discovered before modern methods of archaeological excavation and analysis. Comparison of the dates for the Castanet ceiling and those directly obtained from the Chauvet paintings reveal that the “vulvar” representations from southwestern France are as old or older than the very different wall images from Chauvet.

new scientist seals

Cave paintings in Malaga, Spain, could be the oldest yet found – and the first to have been created by Neanderthals.

Looking oddly akin to the DNA double

helix, the images in fact depict the seals that the locals would have

eaten, says José Luis Sanchidrián at the University of Cordoba, Spain.

They have "no parallel in Palaeolithic art", he adds. His team say that

charcoal remains found beside six of the paintings – preserved in

Spain's Nerja caves – have been radiocarbon dated to between 43,500 and

42,300 years old.

That suggests the paintings may be substantially older than the 30,000-year-old Chauvet cave paintings in south-east France, thought to be the earliest example of Palaeolithic cave art.

The next step is to date the paint

pigments. If they are confirmed as being of similar age, this raises the

real possibility that the paintings were the handiwork of Neanderthals –

an "academic bombshell", says Sanchidrián, because all other cave

paintings are thought to have been produced by modern humans.

Neanderthals are in the frame for the

paintings since they are thought to have remained in the south and west

of the Iberian peninsula until approximately 37,000 years ago – 5000

years after they had been replaced or assimilated by modern humans

elsewhere in their European heartland.

Saturday 23 June 2012

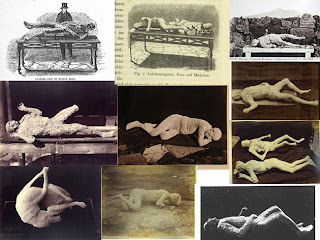

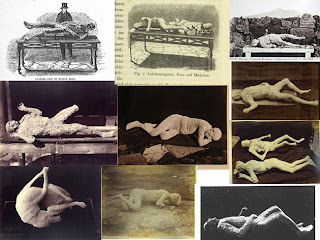

casts / photographs / fearful fidelity / dreadful agony

Delusion & Dream in Jensen's Gradiva 1907

an attempt had been made to cast the body of a woman discovered in the House of the Faun in 1830. The woman's foot seems to have been greatly admired... ma la forma del suo piede e del suo calzare attiro la nostra attenzione / Fiorelli /Dwyer/ Sculpture &Archaeology/ 57

Photography & The Immured Pompeians / The Evolution of Photography/ John Werge / 1890

an attempt had been made to cast the body of a woman discovered in the House of the Faun in 1830. The woman's foot seems to have been greatly admired... ma la forma del suo piede e del suo calzare attiro la nostra attenzione / Fiorelli /Dwyer/ Sculpture &Archaeology/ 57

|

| Add caption |

L'Inconnue de la Seine c.1880s

Eugene Dwyer

Matthew Brady / Battle of Gettysburg 1863

Giuseppe Fiorelli / Casts from Pompei / 1863

Labels:

freud,

gesso,

gradiva,

l'innconue,

petrosomatoglyph,

pompei,

war

kracauer / the last things before the first

History resembles photography in that it is, among other things, a means of alienation..

photography produces artefact, a field of detail, not memory

last

photography produces artefact, a field of detail, not memory

last

The Georgia Guidestone

American Stonehenge: Monumental Instructions for the Post-Apocalypse Wired article

07/0722

A granite monument in rural Georgia has been demolished for safety reasons after being damaged in a blast.

An explosion early on Wednesday reduced one of the slabs at the Georgia Guidestones to rubble.

CCTV footage showed a car leaving the scene and authorities are investigating.

An explosion early on Wednesday reduced one of the slabs at the Georgia Guidestones to rubble.

CCTV footage showed a car leaving the scene and authorities are investigating.

scapegoat

A skeleton recently rediscovered in London's Natural History Museum provides the first evidence that a ritual sacrifice may have taken place at Stonehenge. The remains, which show evidence of beheading, may also throw light on the continuing importance of the megalithic monument, built in three phases between 3050 and 1600 B.C. Radiocarbon analysis indicates that the execution took place in the second half of the seventh century A.D., shortly after the local Anglo-Saxon nobility had converted to Christianity, says David Miles, chief archaeologist at English Heritage, the public agency responsible for the monument's upkeep.

"The beheading suggests that a political or ritual act was taking place at Stonehenge at a time when the henge is thought to have been abandoned and no longer considered a place of significance," says Miles. "Stonehenge is relatively isolated, and a single execution is likely to have been an important symbolic event."

Originally unearthed at Stonehenge in 1923, the male skeleton was believed to have been destroyed during the German bombing of the Royal College of Surgeons in World War II. While researching a book, however, British archaeologist Mike Pitts, a former curator of Avebury Museum in southwest England, found that many skeletons considered lost at the Royal College had, in fact, survived.

When the remains were originally found, scientists assumed the man, aged about 35, had died from natural causes. Recent examination, however, revealed an ancient wound to one of his neck vertebrae, suggesting that he had been beheaded. Pitts believes he may have been a prominent figure, perhaps a king who transgressed the accepted boundaries of religious or political behavior.

Three other skeletons have been discovered at Stonehenge, including the well-preserved remains of a muscular man, aged 25-30, excavated in 1978. This man died from multiple arrow wounds in the third millennium B.C., about the time the Stonehenge megaliths were erected.

| Stonehenge Skeleton Mystery | Volume 53 Number 5, September/October 2000 |

| by Chris Hellier | |

Friday 22 June 2012

The oldest known depiction of Stonehenge

Lucas Deheere 1573-75 I myself have drawn them on the spot British Library Add MS 28330, fol 36

1440? Corpus Christi College MS 194, fol 57

"That year Merlin, not by force but by art, brought and erected the giants' round from Ireland, at Stonehenge near Amesbury". 1440 Douai manuscript Scala Mundi

Folio 30r of British Library, Egerton 3028, a manuscript of English chronicles including an abreviated version the Brut by Wace. This illustration shows the construction of Stonehenge with the assistance of Merlin and is the oldest known illustration of Stonehenge. 1338 -40

British Archaeology

The foundation myth appears in the 12th century. Stonehenge, or Stanenges, is first briefly mentioned c1130 in Historia Anglorum, written by the archdeacon of Lincoln, Henry of Huntingdon, at the command of his bishop Alexander of Blois. "Noone can work out", says Henry, "how the stones were so skilfully lifted up to such a height or why they were erected".

Shortly after, around 1136, Geoffrey of Monmouth wrote his Historia Regum Britanniae, drawing on a vast range of material, from the Venerable Bede to British and continental legends, to build a history of the British kings from the Trojan Brutus up to the 7th century. The immense success of his much copied text shows the deep interest it rapidly inspired.

The passage concerning Stonehenge has often been described, and is well elaborated in Chippindale's Stonehenge Complete (Thames & Hudson, 3rd ed 2004). The legitimate British king, Aurelius Ambrosius, is in exile in Brittany while his usurper Vortigern allies himself with the invading Saxon king Hengist. Vortigern and Hengist arrange a peace meeting at the "cloister of Ambrius" (Amesbury), but the Saxons treacherously slay 460 British lords. Aurelius returns, defeats both Vortigern and Hengist, and seeks a memorial to the dead. Merlin recommends the chorea gigantum, a stone monument on the Irish Mount Killaraus. Only his magic, however, can bring the stones to Amesbury, and he reconstructs them exactly as they were in Ireland. The text shows Aurelius's coronation in c480 and the erection of Stonehenge c485. Later Aurelius and his brother Uther Pendragon (father of Arthur) are buried at Stonehenge.

6 September 2014

Last updated at 04:05

Barack Obama in Stonehenge visit on return from Nato summitThe White House said the presidential helicopter Marine One stopped at

Boscombe Down Airbase, Wiltshire, before his motorcade drove to the

ancient monument.

Mr Obama described seeing the monument as "cool" and said it was something he could tick off his "bucket list".

10 September 2014 Last updated at 01:40

Archaeologists have unveiled the most detailed map ever produced of the earth beneath Stonehenge and its surrounds. They combined different instruments to scan the area to a depth of three metres, with unprecedented resolution. Early results suggest that the iconic monument did not stand alone, but was accompanied by 17 neighbouring shrines. Future, detailed analysis of this vast collection of data will produce a brand new account of how Stonehenge's landscape evolved over time.

enid blyton / christmas book

http://www.silentearth.org/silent-earth-and-pete-glastonbury-film-project/

jubliee

1440? Corpus Christi College MS 194, fol 57

"That year Merlin, not by force but by art, brought and erected the giants' round from Ireland, at Stonehenge near Amesbury". 1440 Douai manuscript Scala Mundi

Folio 30r of British Library, Egerton 3028, a manuscript of English chronicles including an abreviated version the Brut by Wace. This illustration shows the construction of Stonehenge with the assistance of Merlin and is the oldest known illustration of Stonehenge. 1338 -40

British Archaeology

The foundation myth appears in the 12th century. Stonehenge, or Stanenges, is first briefly mentioned c1130 in Historia Anglorum, written by the archdeacon of Lincoln, Henry of Huntingdon, at the command of his bishop Alexander of Blois. "Noone can work out", says Henry, "how the stones were so skilfully lifted up to such a height or why they were erected".

Shortly after, around 1136, Geoffrey of Monmouth wrote his Historia Regum Britanniae, drawing on a vast range of material, from the Venerable Bede to British and continental legends, to build a history of the British kings from the Trojan Brutus up to the 7th century. The immense success of his much copied text shows the deep interest it rapidly inspired.

The passage concerning Stonehenge has often been described, and is well elaborated in Chippindale's Stonehenge Complete (Thames & Hudson, 3rd ed 2004). The legitimate British king, Aurelius Ambrosius, is in exile in Brittany while his usurper Vortigern allies himself with the invading Saxon king Hengist. Vortigern and Hengist arrange a peace meeting at the "cloister of Ambrius" (Amesbury), but the Saxons treacherously slay 460 British lords. Aurelius returns, defeats both Vortigern and Hengist, and seeks a memorial to the dead. Merlin recommends the chorea gigantum, a stone monument on the Irish Mount Killaraus. Only his magic, however, can bring the stones to Amesbury, and he reconstructs them exactly as they were in Ireland. The text shows Aurelius's coronation in c480 and the erection of Stonehenge c485. Later Aurelius and his brother Uther Pendragon (father of Arthur) are buried at Stonehenge.

Historians have spent years debating whether Stonehenge was once a complete circle. Despite numerous tests and excavations, the mystery remained unsolved for almost 5,000 years. But staff at the neolithic site believe the question has finally been answered - all because a hosepipe was too short.

Mr Obama described seeing the monument as "cool" and said it was something he could tick off his "bucket list".

10 September 2014 Last updated at 01:40

Archaeologists have unveiled the most detailed map ever produced of the earth beneath Stonehenge and its surrounds. They combined different instruments to scan the area to a depth of three metres, with unprecedented resolution. Early results suggest that the iconic monument did not stand alone, but was accompanied by 17 neighbouring shrines. Future, detailed analysis of this vast collection of data will produce a brand new account of how Stonehenge's landscape evolved over time.

Buzz Aldrin, the second man on the moon, has a message to Earth: it's

time to go to Mars. He's been broadcasting it loud and clear for years,

but now has made his mission even more majestic by posting this picture

of himself taken at Stonehenge.

| Plaatje van Stonehenge (GMG 432 88) | ||||

| Date | vanaf 1645 | |||

| Source | Biblioteca Nacional Espana | |||

| Author | Blaeu,J |

We promptly sat down with our backs to the sight we had come to see,

& began to eat sandwiches: half an hour afterwards we were ready to

make our inspection.

http://www.silentearth.org/silent-earth-and-pete-glastonbury-film-project/

Thursday 21 June 2012

The Collas Machine / appareil réducteur

The Collas Machine

Invented in 1836 by French engineer Achille Collas, this machine uses a pantograph system to make proportionately larger or smaller duplications of a sculpture. The concept can be traced to ancient Greek and Roman artists, who wanted to reproduce the perfect proportions of the human figure in their sculpture. Their method was called pointing, which meant that measurements of the desired figure were taken, then proportionally increased or decreased on a model. Collas machines often look like lathes. On one turntable sits the plaster model. On a second turntable, connected to the first, sits a clay or plaster "blank" that has been roughly shaped to resemble the model but on a larger or smaller scale.

Invented in 1836 by French engineer Achille Collas, this machine uses a pantograph system to make proportionately larger or smaller duplications of a sculpture. The concept can be traced to ancient Greek and Roman artists, who wanted to reproduce the perfect proportions of the human figure in their sculpture. Their method was called pointing, which meant that measurements of the desired figure were taken, then proportionally increased or decreased on a model. Collas machines often look like lathes. On one turntable sits the plaster model. On a second turntable, connected to the first, sits a clay or plaster "blank" that has been roughly shaped to resemble the model but on a larger or smaller scale.

The

Collas machine keeps the model and the blank in the same orientation as

the technician uses a tracing needle, linked to a sharp

cutting instrument, or stylus, to transfer a succession of profiles

from the model onto the blank. Gradually the blank is worked so that it becomes a larger or smaller duplicate of the model.

Rodin and his skilled associate Henri Lebossé collaborated closely on reductions and enlargements

Around 1836 Collas developed a new machine permitting the mathematically precise reduction or enlargement of sculptural objects in full relief. Three years later he demonstrated its abilities by producing a two-fifths size reproduction of the Venus de Milo. His device became the main vehicle for the mass replication of antique and modern sculptures catering for a growing demand for inexpensive luxury items to decorate bourgeois interiors. In 1838 he entered into partnership with the manufacturer Ferdinand Barbedienne (1810-92) and the firm of Collas eventually employed around 300 workers and produced over a thousand bronzes each year. They reached an international audience with an acclaimed exhibit at the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London, which featured as its centre-piece a half-size reproduction of Ghiberti's principal door to the Baptistery in Florence. Even after Collas's death in 1859, his 'method' remained the mainstay of Barbedienne's enduring commercial success throughout the latter part of the nineteenth century.

Rodin and his skilled associate Henri Lebossé collaborated closely on reductions and enlargements

Around 1836 Collas developed a new machine permitting the mathematically precise reduction or enlargement of sculptural objects in full relief. Three years later he demonstrated its abilities by producing a two-fifths size reproduction of the Venus de Milo. His device became the main vehicle for the mass replication of antique and modern sculptures catering for a growing demand for inexpensive luxury items to decorate bourgeois interiors. In 1838 he entered into partnership with the manufacturer Ferdinand Barbedienne (1810-92) and the firm of Collas eventually employed around 300 workers and produced over a thousand bronzes each year. They reached an international audience with an acclaimed exhibit at the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London, which featured as its centre-piece a half-size reproduction of Ghiberti's principal door to the Baptistery in Florence. Even after Collas's death in 1859, his 'method' remained the mainstay of Barbedienne's enduring commercial success throughout the latter part of the nineteenth century.

Cheverton reducing machine

Benjamin Cheverton

Cheverton demonstrated his reducing machine at the Great Exhibition in 1851 and won a gold medal for his copy of Theseus from the Elgin collection in the British Museum.

The reducing machine provided the technical means of allowing sculptures to be replicated in parian ware by Minton's and other pottery manufacturers or in materials such as alabaster and ivory.

In sculpture, a three-dimensional version of the pantograph was used,[3] usually a large boom connected to a fixed point at one end, bearing two rotating pointing needles at arbitrary points along this boom. By adjusting the needles different enlargement or reduction ratios can be achieved. This device, now largely overtaken by computer guided router systems that scan a model and can produce it in a variety of materials and in any desired size,[4] was first invented by inventor and steam pioneer James Watt (1736–1819) and perfected by Benjamin Cheverton (1796–1876) in 1836. Cheverton's machine was fitted with a rotating cutting bit to carve reduced versions of well-known sculptures.[5] Of course a three-dimensional pantograph can also be used to enlarge sculpture by interchanging the position of the model and the copy.[6][7]

Cheverton demonstrated his reducing machine at the Great Exhibition in 1851 and won a gold medal for his copy of Theseus from the Elgin collection in the British Museum.

The reducing machine provided the technical means of allowing sculptures to be replicated in parian ware by Minton's and other pottery manufacturers or in materials such as alabaster and ivory.

In sculpture, a three-dimensional version of the pantograph was used,[3] usually a large boom connected to a fixed point at one end, bearing two rotating pointing needles at arbitrary points along this boom. By adjusting the needles different enlargement or reduction ratios can be achieved. This device, now largely overtaken by computer guided router systems that scan a model and can produce it in a variety of materials and in any desired size,[4] was first invented by inventor and steam pioneer James Watt (1736–1819) and perfected by Benjamin Cheverton (1796–1876) in 1836. Cheverton's machine was fitted with a rotating cutting bit to carve reduced versions of well-known sculptures.[5] Of course a three-dimensional pantograph can also be used to enlarge sculpture by interchanging the position of the model and the copy.[6][7]

Sunday 10 June 2012

Wednesday 6 June 2012

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)